Old French Lady By The River, A Travel Article on New Orleans

While doing some research on Jackson Square to add some info about my Jackson Square paintings in my Blog I ran across an article written around 1913 by a visitor to New Orleans published in a travel book back then. In fact I found the book itself for sale on E-Bay but it was way too costly for me. It is a rare book and I hope the New Orleans Public Library has a copy. To help preserve what was said about my city then I am reproducing the article on New Orleans here for everyone to read as it applies just as much today as it did 95 years ago. When I paint things I like to know more than just what I see, some history or story to get the spirit of what I paint. Viewing my Jackson Square paintings I think I capture that unique spirit of New Orleans as described in this article.

Below it is an old video on New Orleans Travel from 1940, you can scroll down to it and see what New Orleans looked like in 1940.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

New Orleans:

The Old French Lady On The River

--------------------------------------------------------------

From "The Personality of American Cities" By Hungerford, Edward, 1875-1948 Publisher New York : McBride, Nast & Company 1913, Not In Print,

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

At the bend of the river she stands — this drowsy old French lady of the long ago. They have called her the Crescent City. But the Mississippi makes more than a single turn around the wide-spreading town. And the results are most puzzling, even to those steady-minded folk who assert that they are direction-wise. In New Orleans, east seems west and north seems south. It must almost be that the Father of Rivers reverses all the laws of Mother Nature and runs his course upstream.

New Orleans is upon the east bank of the Mississippi. All the guide-books will tell you that. But in the morning the sun arises from over across the river, and in the cool of evening his reddish radiance is dying over Lake Ponchartrain, directly east from the river at least, so your direction wise intelligence seems to tell you. But east is east and west is west and Old Sol has made such a habit of rising and setting these many thousand years that his reliability is not to be trusted. As to the reliablity of the Father of Waters there is quite another matter.

Truth to tell, the Mississippi river is probably the most utterly unreliable thing within the North American continent. He has shifted his course so many times within the brief century that the white-skinned men have known him, that the oldest of them have lost all trace of his original course. And so to steer a vessel up and down the stream is a doubly difficult art. The pilot does not merely have to know his steering-marks — the range between that point and this, the thrust of some hidden and fearfully dangerous reef, the advantage to be gained between eddies and currents for easy running he has to learn the entire thing anew each time he brings a craft up or down the river. Mark Twain has long since immortalized the ample genius of the Mississippi pilots. The stories of the river's unreliability, of its constant tendency to change its channel are apocryphal — almost as old as the oldest of the houses of old New Orleans. And this is not the story of the river.

Yet it must not be forgotten that the river almost is New Orleans, that from the beginning it has been the source of the French lady's strength and prosperity. Before there was even thought of a city the river was there pouring its yellow flood down from an unknown land to the great gulf. Bienville, the real founder of New Orleans, saw with the prophetic sight of a really great thinker what even a river that came to the sea from an unexplored land might mean in years to come to the city of his creation. His prophecy was right. When the river, with the traffic upon its bosom, has prospered, New Orleans has prospered. And in the lean years when the river traffic has dwindled, New Orleans has felt the loss in her every fiber. There are old-timers in the city who shake their heads when they tell you of the fat river-boats crowding in at the levee, of the clipper-ships and the newer steam-propelled craft at the deeper docks, of the crowds around the old St. Louis and the St. Charles Hotels, the congested narrow streets, the halcyon days when the markets of the two greatest nations in the world halted on the cotton news from Factors Row. And New Orleans awaits the opening of the Panama canal with something like feverish anticipation, for she feels that this mighty nick finally cut into the thin neck of the American continents, her wharves will again be crowded with shipping — this time with a variety of craft plying to and from the strange ports of the Pacific. So much does her river still mean to her.

Factors Row still stands, rusty and somewhat grimed. No longer is it consequential in the markets of the world. In fact, to put a bald truth baldly, no longer is New Orleans of supreme consequence in the cotton problem of all nations. A great cotton shipping port she still is and will long remain. But the multiplication of railroad points and the rapid development of such newer cotton ports as Galveston, to make a single instance, have all worked against her preeminence.

This is not a story of the commercial importance of New Orleans, either. There are plenty who are willing to tell that story, with all of its romantic traditions of the past and its brilliant prophecies for the future. This is the story of the New Orleans of today, the city who with an almost reverential respect for the Past and its monuments still holds her doors open to the Present and its wonders.

Of the Past one may know at every turn. North of Canal street — that broad thoroughfare which ranks as a dividing path with Market street in San Francisco — the city has changed but little since the Civil War. South of Canal still called the "new " part of the city there has been some really modern development. Prosperous looking skyscrapers have lifted their lordly heads above the narrow streets and the compactly built "squares " which they encompass ; there are several modern hotels with all the momentary glory of artificial marbles and chromatic frescoes, department stores with show windows as brave and gay as any of those in New York or Chicago or Boston. But even if the narrow streets were to be widened, New Orleans would never look like Indianapolis or Kansas City or St. Paul — any of the typical cities of the so-called Middle West. Too many of her stout old structures of the fifties and the sixties still remain. And hung upon these, uncompromising and triumphant, are the galleries.

The galleries of New Orleans! They are perhaps the most typical of the outward expressions of a town whose personality is as distinct as that of Boston or Charles-ton or San Francisco. They must have been master workmen whose fingers and whose ancient forges worked those delicate and lacelike traceries. And it has been many thankful generations who have praised the practical side of their handicraft. For in the long hot summer months of New Orleans these galleries furnish a shade that is a delight and a comfort. On rainy days they are arcades keeping dry the sidewalks of the heart of the town. And from the offices within, the galleries, their rails lined with growing things, are veritable triumphs. Once in a great while some one will rise up and suggest that they be abolished — that they are old-fashioned and have long since served their full purpose. That some one is generally a smart shopkeeper who has drifted down from one of these upstart cities from the North or East. But New Or-leans is smarter still. She well knows the commercial value of her personality. There are newer cities and showier within the radius of a single night's ride upon a fast train. But where one man comes to one of these, a dozen alight at the old French town by the bend of the yellow river.

" Give J a few French restaurants, some fame for its cocktails or its gin-fizzes just as New Orleans has and I will bring a dozen big new factories here within the next three years," said the secretary of the Chamber of Commerce of a thriving Texas town the other day. He knew whereof he spake. And now, we shall know whereof we speak. We shall give a moment of attention to the little restaurants and the gin-fizzes.

Let the gin-fizzes come first, for they are nearly as characteristic of the old town as her galleries ! You will find their chief habitat just across a narrow alley from the St. Charles Hotel. There is a long bar on the one side of the room, upon which stand great piles of ice-bound southern oysters — twelve months of the year, for New Orleans never reads an " R " in or out of her oyster-eating calendar. But any bar may bring forth oysters, and only one bar in the world brings forth the real New Orleans gin-fizz. Two enterprising young men stand behind the bar-keepers in a perpetual shaking of the fizzes. If it is tantalizing to shake that whereof you do not taste, they show it not. And in the hours of rush traffic there are six of the non-bar-keeping bartenders who give the correct amount of ague to New Orleans' most delectable beverage. A hustler from North or East would put in electric shakers instanter — a thousand or is it ten thousand revolutions to the minute? He would brag of his electric shakers and the New Orleans gin-fizz would be dead — forever. Romance and an electric shaker cannot go hand in hand.

" The ingredients? " you breathlessly interrupt. " The manner of the mixing? "

Bless your heart, if the Gin Fizz House published its close-held secret to the world, it would lose its chief excuse for existence and then become an ordinary drinking-place. As it is, it holds its head above the real variety of saloons, even above the polished mahogany bar of the aristocratic hotel across the narrow street. For its product, if delightful, is still gentle, although insidious, perhaps. It is largely milk and barely gin. You can drink it by the barrel without the slightest jarring of your faculties. And it is rumored that some of the men of New Orleans use it as a breakfast-food.

From the Gin Fizz House to the Absinthe House is a long way,— in more meanings than one. The Absinthe House is hardly less famed, but in these days when drinking has largely gone out of fashion and worm-wood is under the particular ban of the United States statutes, it is largely a relic of the past. It stands in the heart of the old French town and before we come to its broad portal, let us study the fascinating quarter in which we are to find it.

We have already spoken of Canal street, so broad in contradistinction to the very narrow streets of the rest of the older parts of the town, that one can almost see the narrow water-filled ditch that once traversed it, as the dividing line of the city. South of Canal street, the so-called American portion of the city, with many affectations of modernity north of that thoroughfare curiously enough the down stream side the French quarter, architecturally and romantically the most fascinating section of any large city of the United States. The very names of its streets Chartres, Royal, Bourbon, Burgundy, Dauphine, St. Louis quicken anticipation. And anticipation is not dulled when one comes to see the great somber houses with their mysterious and moth-eaten courtyards and the interesting folk who dwell within them.

We choose Royal street, heading straight away from Canal street as if in shrinking horror of electric signs and moving picture theaters. In a single square they are behind and forgotten and, if it were not for the trolley cars and the smartly dressed French girls, we might be walking in Yesterday. The side streets groan under the same ugly, heavy patterns of Belgian block pavement that have done service for nearly a century. Originally the blocks brought long years ago as ballast in the ships from Europe were in a pretty pattern, laid diagonally. But heavy traffic and the soft sub-strata of the river-bank town have long since worked sad havoc with the old pavements. And a new city administration has finally begun to replace them with the very comfortable but utterly unsentimental asphalt.

Here is the Absinthe House, worth but a single glance, for it has descended to the estate of an ordinary corner saloon. Only ordinary corner saloons are not ordinarily housed in structures of this sort. You can see houses like this in the south of France and in Spain — so I am told. For below Canal street is both French and Spanish. Remember, if you please, that the French of the Southland shared the same hard fate of their countrymen in that far northern valley of the great St. Lawrence neglect. The French are the most loyal people on earth. Their fidelity to their language and their customs for nearly two centuries proves that. That faith, steadfast through the tragedy of the indifference and neglect of their mother country, doubly proves it. And the only difference between the French-man of Quebec and the Frenchman of New Orleans was that in the South the Spaniard was injected into the problem. But the Frenchman in the South was not less loyal than his fellow-countryman of the North. A dissolute king sitting in the wreck of his great family in the suburbs of Paris might barter away the title of his lands, but no Louis could ever trade away the loyalty of the older French of New Orleans to their land and its institutions. In such a faith was the French quarter of the city born. In such faith has it survived, these many years. And perhaps the very greatest episodes in the history of the city were in those twenty days of November, 1803, when the French flag displaced the Spanish in the old Place d'Armes, to be replaced only by the strange banner of a newborn nation which was given the opportunity of working out the destiny of the new France.

So it was the Spaniard who took his part in the shaping of the French quarter of New Orleans. You can see the impress of his architects in the stout old houses that were built after two disastrous and wide-spread fires in the closing years of the eighteenth century — even in the great lion of the town ; the Cabildo which rises from what was formerly the Place d'Armes and is today Jackson square. And the old Absinthe House, with its curiously wrought and half-covered courtyard is one of these old-time Spanish houses.

Now forget about the absinthe as the rest of the French folk of the land are beginning to forget it and turn your attention to the courtyards. In another old Southern city — Charleston — the oldest houses shut the glories of their lovely aging gardens from the sight of vulgar passers by upon the street by means of uncompromising high fences. The old houses of New Orleans do more. Their gardens are shielded from the crowded, noisy, horrid streets by the houses themselves. And he who runs through those crowded, noisy, horrid streets, must really walk, for only so will he catch brief glimpses of the glories of those fading courtyard gardens.

Sometimes, if you have the courage of your convictions and the proper fashion of seizing opportunity by the throat you may wander into one of the tunnel-like gateways of one of these very old houses. No one will halt you.

Here it is — old France in new America. The tunnel-like way from the street is shady and cool. From it leads a stair to the right and the upper floor of the house, a stair up which a regiment might have walked, and down which the old figure of a Balzac might descend this moment without ever a single jarring upon your soul. The stair ends in a great oval hall, whose scarlet paper has long since faded but still remains a memory of the glories of the days that were. The carved en-tablatures over the doors, the bravado of cornice and rosette where the plaster has not finally fallen, proclaim the former grandeur of this apartment. And in some former day a great chandelier must have hung from the center of its graceful ceiling. Today some one of the neighboring antique stores has reaped its reward, and a candle set in a wall-lantern is its sole illumination. A shabby room will not bear the glories of a gay chandelier. And the old Frenchman and his wife who live in the place have all but forgotten. They have a parrot and a sewing-machine and what are the glories of the past to them?

Of course, such a house must have its courtyard. And if the huge copper-bound tank is dry, and the water has not forced its way through the battered fountain these many years, if the old exquisite tiles of the house long since went to form the roof of the new garage of some smart new American place up the river — the magnolia still blossoms magnificently among the decay, and Madame's skill with her jessamine and her geraniums would confound the imported tricks of those English gardeners in the elaborate new places.

Here then is the old France in the new land the priceless treasure that New Orleans wears at her very heart. And here in the very heart of that heart is an ugly old building boarded up by offensively brilliant advertising signs.

An ugly old building did we say, with rough glance at its rusty façades? Can one be young and beautiful forever? Rusty and beautiful oh no, do not scorn the old St. Louis Hotel for following the most normal of all the laws of Nature. For within this moldering and once magnificent tavern history was made. In one of its ancient rooms a President of the United States was unmade, while in another chamber human life was bought and sold with no more concern than the old Creole lady on the far corner shows when she sells you the little statues of the Blessed Virgin.

These wonders are still to be seen for the asking. The concierge of the old hotel is a courteous lady who with her servant dwells in the two most habitable of its remaining rooms. There is no use knocking at the hotel door for she is very, very deaf indeed, poor lady. But if you will brave a stern " No Admittance" sign and ascend the graceful winding stair for a single flight such a stair as has rarely come to our sight you will find her ready and willing. One by one she shows you the rooms, faded and disreputable, for the hotel is in a fearful state of disrepair. The plaster is falling here and there, and where it still adheres to the lath the old-time paper hangs in long shreds, like giant stalactites, from the ceiling. Once, for a decade in the "late eighties," an effort was made to revive the hotel and its former glories a desperate and a hopeless effort and the pitiful " innovations " of that régime still show. But when you close your eyes you do not see the St. Louis Hotel of that decade, but rather in those wonderful twenty years before the coming of the cruel war. In those days New Orleans was the gayest city in the new world, uptilting its saucy nose at such heavy eastern towns as New York or Boston. Its wharves were crowded with the ships of the world, the riverboat captains fought for the opportunity of bringing the mere noses of their craft against the overcrowded levee. Cotton — it was the greatest thing of the world. New Orleans was cotton and cotton was the king of the world.

No wonder then that the St. Louis Hotel could say when it was new, that it had the finest ballrooms in the world. They still show them to you, in piecemeal, for they were long since cut up into separate rooms. The great rotunda was ruined by a temporary floor at the time the state of Louisiana bought the old hotel for a capitol, and used the rotunda for its fiery Senate sessions.

All these things the concierge will relate to you — and more. Then she takes you down the old main-stair, gently lest its rotting treads and risers should crumble under too stout foot-falls. Into the cavernous bottom of the rotunda she leads you. It is encumbered with the steam-pipes of that after era, blocked with rubbish, very dark withal. The concierge, with a fine sense of the dramatic, catches up a bit of newspaper, lights it, thrusts it ahead as a lighted torch.

" The old slave mart," she says, in a well-trained stage whisper, and thrusts the blazing paper up at full arm's length. As the torch goes higher, her voice goes lower : " Beyond the auction block, the slaves' prison."

As a matter of real fact, the " slaves' prison " is probably nothing more or less than the negro quarters that every oldtime southern hotel used to provide for the slaves of its planter patrons. But the concierge does not overlook dramatic possibilities. And she is both too deaf and too much a lady to be contradicted. She has given you full value for the handful of pennies she expects from you. And as for you — a feeling of some-thing like indignation wells within you that the city of New Orleans has permitted the stoutly built old hotel to fall into such ruin. In an era which is doing much to preserve the monuments of the earlier America, it has been overlooked.

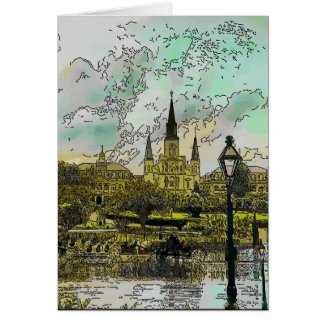

Such resentment softens a little further down. You are in Jackson square now —the Place d'Armes of the old French days — and facing there the three great lions that have stood confronting that open space since almost the beginning of New Orleans. The great cathedral flanked by the Cabilda and the Presbytery is not, of itself, particularly beautiful or impressive. But it is interestng to remember that within it on a memorable occasion Andrew Jackson sat at mass interesting because he had just fought the battle of New Orleans and ended the Second War with England. And the Te Deum that went up at that time was truly a thankful one. The Cabilda and the Presbytery, invested as they are with rare historical interest, are more worth while.

But to our mind the chief delight of Jackson square are the two long red-brick buildings that completely fill the north and south sides of that delectable retreat. In themselves these old fellows are not architecturally important, although by close inspection you may find in the traceries of their gallery rails the initials of the wife of the Spanish grandee Madama de Pontalba historically they are not distinguished, unless count the fact that in one of them dwelt Jenny Lind upon the occasion of a not-to-be-forgotten engagement in New Orleans but as the sides of what is perhaps the most delightful square in the entire Southland they are most satisfying. Jackson square has fallen from its high estate. Its gardens were once set out in formal fashion for the elect of New Orleans, nowadays they are visited by swarms of the cheaper French and Italian lodgers of the neighborhood, and scrawny felines from the old Pontalba buildings use it as a congregating place. But, even in decadent days, its fascination is none the less.

Beyond Jackson square rests the French market, the very index to all that New Orleans' love of good eating that has become so closely linked with the city. The market-scheme of the city as this is being written is being greatly revised. Up to the present time the market-men have been autocrats. The grocers of the city have been forbidden to sell fresh fruits or vegetables; if a retailer be audacious enough to wish to set out with a private market, he must be a certain considerable number of squares distant from a public institution—and pay to the city a heavy license fee as penalty for his audacity. Nor is that all. The consumer is for-bidden to purchase direct from the producer, even though the producer's wagon be backed up against the market curb in most inviting fashion. New Orleans recognizes the middleman and protects him or has protected him until the present time. Even peddlers have been barred from hawking their wares through her streets until noon when the public markets close and the housewives have practically completed their purchases for the day.

But banish the thoughts of the markets as economic problems, cease puzzling your blessed brains with that eternal problem of the cost-of-living. Consider the French market as a truly delectable spot. Go to it early in the morning, when the sun is beginning to poke his way down into the narrow streets and the shadows are heavy under the galleries. Breakfast at the hotel? Not a bit of it.

You take your coffee and doughnuts alongside the market men at long and immaculate counters in the market-house. And when you are done you will take your oath that you have never before tasted coffee. The coffee man bends over you he is a coffee man descended from coffee men, for these stalls of the famous old markets are almost priceless heritages that descend from generation to generation. In these days they never go out of a single family.

"Café lait?" says the coffeeman.

You nod assent.

Two long-spouted cans descend upon your cup. From one the coffee, from the other creamy milk come simultaneously, with a skill that comes of long years of practice on the part of the coffeeman.

That is all —café lait and doughnuts. They make just as good doughnuts in Boston, but New England has never known the joys of café lait. If it had, it would never return to its oldtime coffee habits. And the older markets of Boston do not see the fine ladies of the town coming to them on Sunday morning, after mass, negro servants behind, to do their marketing, themselves.

Hours of joy in this market the food capital of a rich land of milk and honey. After those hours of joy breakfast at the Madame's.

The Madame began — no one knows just how many years ago by serving an eleven o'clock breakfast to the market-men, skilled in food as purveyors as most critical of the food they eat. The Madame realized that problem and met it. So well did she meet it that the fame of her cookery spread outside the confines of the market-houses, and city folk and tourists began drifting to her table. In a few years she had established an institution. And today her breakfast is as much a part of New Orleans as the old City Hall or the new Court House.

She has been dead several years dear old gastronomic French lady but her institution, after the fashion of some institutions, lives after her. It still stands at the edge of the market and it still serves one meal each day the traditional breakfast. It is sad to relate that it has become a little commercialized they sell souvenir spoons and cook-books — but you can shut your eyes to these and still see the place in all of its glories.

A long, low room at the back of and above a little saloon, reached from the side-door of the saloon by a turning and rickety stair. A meagerly equipped table in the long, low room, from which a few steps lead up to a smoky but immensely clean kitchen. From that kitchen odors. Odors? What a name for incense, the promise of preparation. You sometimes catch glimpses of busy women, fat and uncorseted. Cooks?

Perish the words. These are artists, if artists have ever really been.

Finally and upon the stroke of eleven the breakfast. It shall not be described here in intimate detail for you, dear reader, will not be sitting at the Madame's hospitable table as you read these lines. It is enough for you to know that the liver is unsurpassable and the coffee the coffee gets its flavor from an adroit sweetening of cognac and of sugar. What matter the souvenirs now? The breakfast has lost none of its savor through the passing of the years.

For here is New Orleans where it seems impossible to get a poor meal. There is many and many an interior city of size and pretentious marbleized and flunkeyized hotels of which that may not be said. But in New Orleans an appreciation of good cookery is an appreciation of the art of a real profession. And of her restaurants there is an infinite variety La Louisiane, Galatoire's, Antoine's, Begue's, Brasco's the list runs far too long to be printed here. Nor does the space of this page permit a recountal of the dishes themselves the world famed gumbos, the crawfish bisque, the red-snapper stuffed with oysters, the crabs and the shrimps. And lest we should be fairly suspected of trying to emu-late a cook-book, turn your back upon the fine little restaurants, where noisy orchestras and unspeakable cabarets have not yet dared to enter, and see still a little more of the streets of the old French quarter.

More courtyards, more old houses, a venerable hall now occupied by a sisterhood of the Roman church but formerly gay with the " quadroon balls " which gave spicy romance to all this quarter. And here, rising high above the narrow thrust of Bourbon street, the French Opera, for be it remembered that New Orleans had her opera house firmly established when New York still regarded hers as a dubious experiment. To come into the old opera house, builded after the impressive fashion of architects of another time, with its real horseshoe and its five great tiers rising within it — is again to see the old New Orleans living in the new. It is to see the exclusive Creoles perhaps the most exclusive folk in all America half showing themselves in the shadowy recesses of their boxes. And to be in that venerable structure upon the night of Mardi Gras is to stand upon the threshold of a fairy world.

It is not meet that the details of the greatest annual carnival that America has ever known should be fully described here. It is enough here and now to say that New Orleans merely exists between these great parties at the eve of each Lent; that nearly a twelvemonth is given to preparations for the Mardi Gras. One festa is hardly done before plans are being made for the next — rumor runs slyly up and down the narrow streets, costumiers are being pledged to inviolate secrecy, strange preparatory sounds emerge from supposedly abandoned sheds and houses, rumors multiply, the air is surcharged with secrecy. Finally the night of nights. Canal street, which every loyal resident of New Orleans believes to be the finest parade street in all the world, is ablaze with the incandescence of electricity, a-jam with humanity. For a week the trains have been bringing the folk in from half-a-dozen neighboring states by the tens of thousands. There is not a single parish of venerable Louisiana without representation; and more than a fair sprinkling of tourists from the North and from over-seas.

Finally after Expectancy has almost given the right hand to Doubt, the fanfare of trumpets, the outriders of Parade. From somewhere has come Rex and The Queen and all the Great and all the Hilariously Funny and the rest besides. From the supposedly abandoned sheds and houses, from the costumiers? Do not dare to venture that, oh uncanny and worldly minded soul !

Fairyland never emerged from old sheds, a King may not even dream of a costumier. From thin air, from the seventh sense, the land of the Mysterious, this King and Queen and all their cavalcade. Then, too, the Royal Palace the historic French Opera House floored and transformed for a night. More lights, more color, the culinary products of the best chefs of all the land working under a stupendous energy, music, dancing, white shirts, white shoulders, gayety, beauty — for tomorrow is Ash Wednesday, and Catholic New Orleans takes its Lent as seriously as it gaily takes the joyousness of its carnivals.

For three-quarters of a century these carnivals have been the outspoken frivols of the old French lady by the bend of the yellow river. In all that time the carnival has progressed until it today is the outward expression of the joyousness of a joyous city. In all that time did we say? There was an interregnum the Four Years. In the Four Years the little French restaurants were closed, the lights at the Opera extinguished there could be no Carnival, for Tragedy sat upon the South-land. And in a great house in Lafayette square there sat a man from Massachusetts who ruled with more zeal than kindness. And that man New Orleans has not forgotten — not even in the half-century that has all but healed the sores of the Four Years.

" It is funny," you begin, "that New Orleans should make so much of the Boston Club, when Butler came from —"

It is not funny. You saw the Boston Club which vies for social supremacy in the old French city with the Pickwick Club, there in Canal street, at least you saw its fine old white house in that broad thoroughfare.

It is not funny. Your New Orleans man tells you — courteously but clearly.

We named our club from that game," he says.

" Boston was a fine game, sir," he adds. "And that without ever a thought of that town up in Massachusetts."

From a carnival to a graveyard is a far cry indeed, and yet the cemeteries of New Orleans are as distinctive of her as her Mardi Gras festivities. We have spoken of the river and the great part it has played in the history of the city that rests so close to its treacherous shore. And it is that very treacherous shore that makes it so exceedingly difficult to arrange a cemetery in the soft and marshy soil on which the city is built.

So it is that the New Orleans' cemeteries are veritable cities of the dead. For the bodies that are buried within them are placed above the ground, not under them. Tombs and mausoleums are the rule, not the exception, and where a family is not prosperous enough to own even the simplest of tombs, it will probably join with other families or with some association in the ownership of a house in the city of the dead. And for those who have not even this opportunity there are the ovens.

The ovens are built in the great walls that encompass the older cemeteries and make them seem like crumbling fortresses. Four tiers high, each oven large enough to accommodate a coffin the sealed fronts bear the epitaphs of those who have known the New Orleans of other days. A motley company they are — poets, pirates, judges, planters, soldiers, priests around them the scarred regiments of those who lived their lives without the haunting touch of Fame upon the shoulder no one will even venture a guess as to the number that have been laid away within a single one of these cities.

And when you are done with seeing the graves of Jean Lafitte or Dominique You why is it that the average mind pricks up with a more quickened interest at the tomb of a pirate than at a preacher — the Portuguese sexton begins plucking at the loosely laid bricks of one of these abandoned ovens. Abandoned? He lifts out a skull, this twentieth century Yorick and bids you peep through the aperture. Like the concierge of the old hotel, looking is made more easy from a blazing folding copy of the morning Picayune. In the place are seemingly countless skulls, with lesser bones.

" He had good teeth, this fellow," coughs the Portuguese.

You do not answer. Finally " Do they bury all of them this way? "

Not at first, you find. The strict burial laws of New Orleans demand that the body shall be carefully sealed and kept within the oven for at least a year. After that the sexton may open the place, burn the coffin and thrust the bones into the rear of the place. And New Orleans can see nothing unusual in the custom.

" New Orleans is more like the old San Francisco than any other community I have ever seen," says the Californian. Not in any architectural sense and of course two cities could hardly be further apart in location than the city in the flat marshlands whose trees are below the level of the yellow river at flood-tide, and the new city that rises on mountainous slopes from the clear waters of the Golden Gate. But there is an in-tangible likeness about New Orleans and his city that was but never again can be, that strikes to the soul of the Californian. Perhaps he has come to know something of the real life of the Creoles — of those strange folk who even today can say that they have lived long lives in New Orleans and never gone south of Canal street. Perhaps he has met some of that little company of old French gentlemen who keep their faded black suits in as trim condition as their own good manners, and who scrimp and save through years and months that they may visit not Chicago or New York but Paris, Paris the unutterable and the unforgettable.

" New Orleans is more like the old San Francisco than any other community that I have ever seen," reiterates the Californian. " It is more like the old than the new San Francisco can ever become."

And there is a moral in that which the San Franciscan speaks. In the twinkling of an eye the old San Francisco disappeared forever. Slowly, but surely, the old New Orleans is beginning to fade away. There are indubitable signs of this already. When it shall have gone, our last stronghold of old French customs and manners shall have gone. One of the most fascinating chapters in the story of our Southland will have been closed.

New Orleans Jackson Square

by figstreetstudio

Labels: Mississippi River, new orleans, travel